The modern internet is a firehose of transient information.

Twitter, Substack, Hacker News, Reddit, rinse-and-repeat. Right-click, open link in new tab. Your browser tabs continue to expand outward. The titles are no longer visible, compressed by an ever-growing work queue. Only a little glyph remains to indicate each tab, playfully teasing you with a “hey, I’m still here”.

You want to keep up, but you can’t. At some point, you have to declare browser bankruptcy.

Often this is done by accidentally closing your browser, followed by a frantic attempt to dig up the forgotten sites.

Rarely, but sometimes, you do this on purpose. A hard reset. A detox for your digital diet. Close every tab, and pray that none of them were important to your work.

Spoiler: they weren’t.

You really didn’t need to waste time reading that obscure 30 page research paper or that paywalled article about the NextBigThing™.

It’s no surprise to anyone at this point that our most scarce resource is not time, but attention.

Most modern megacorps feed on this idea.

We all have only 24 hours in the day and we need to work, eat and sleep. That puts a hard limit on how much human attention exists. At the same time digital technologies are producing unprecedented amounts of information that we could pay attention to. On Youtube alone 100 hours of video is uploaded every minute1. Increasingly you can measure how valuable something is by how much attention it controls (e.g., Google, Facebook, etc).

Albert Wenger, “Land, Capital, Attention: This Time it Is the Same”

Google serves hyper-optimized advertising. The salesman who used to have to peddle door-to-door now lives within your laptop, ruthlessly showing one item after another. His catalog, endless. Every search might as well be an infomercial.

Through this lens, we can understand Zuckerberg’s costly desire to conquer the metaverse. Once you put on an Oculus headset, Meta has a say in what you see, hear, and choose to do. An immersive metaverse is essentially an attention trap.

Of the 24 hours in the day, you only have a handful of focused hours and a limited amount of energy. You cannot afford to drain these to attention traps.

Narrowing In

So how can we best decide how to spend our attention? How do we avoid attention traps?

I suspect the answer has to do heavily with curation. The amount of content available for consumption is enormous. Successive filters of curation must be applied to the endless streams of information available online to capture the personally relevant signal in the noise.

There are two types of curation: algorithmic and human.

Most algorithmically-curated feeds (e.g. most social media sites) don’t have your best interests at heart. Remember, they want to hold your attention for as long as they can. You are the product. In the limit, these feeds prioritize sensational content or promote echo chambers, which can lead to a skewed perception of reality and increased polarization.

Facebook has been criticized for its role in spreading misinformation and reinforcing users' existing beliefs, while YouTube's recommendation algorithm has been known to lead users down rabbit holes of increasingly extreme content.

Most productive people recognize that they are not immune to these algorithmically-curated feeds, and actively combat them by avoiding social media altogether or using a whole kitchen sink of tools to fight back.

The challenge with human-curated feeds (e.g. Substack, newsletters) is that they’re often still too big. As much as I enjoy weekly round-ups, I rarely have the time (or attention) to consume everything provided. At this point, I'm subscribed to too many interesting people and receive too many incredible newsletters.

But that brings me back to square one: there's just too much information out there. Subscribing to multiple newsletters on the same topic can lead to an overwhelming amount of content, making it difficult to prioritize what to read and causing important information to be missed.

I don't want to read/watch everything, but I also don't want to miss the important details. It's suffocating2.

Another issue is novelty. My favorite reads sometimes have nothing to do with my work, current interests, or hobbies. Reading back-to-back papers on language models can be exhausting. Jamming an essay about New York City construction in between is refreshing.

My best source for information (by far, and perhaps surprisingly) has been iMessage.

It’s Filters All The Way Down

There's something about not just human-filtered information, but friend-filtered information. I love reading things that are sent to me by my pre-med friends, because it's usually high signal and generally not something I would have found in my Twitter feed.

This, at its core, is the challenge of recommendations, which I wrote about in a previous piece. We want to be surprised by new content, but algorithms want to comfort us with media that we and our mostly homogeneous friends have approved.

I would pay for a news reader that had two key features:

Options to follow different topics and people. You get to pick which channels of information interest you.

Every morning/evening it pings me with 3-5 articles I should read. Some should be highly recommended by friends, others should be strange and somewhat out of the blue. Curveballs are helpful.

These articles don’t necessarily have to be from the same day (in fact, preferably not). Most of the best essays were written a while back. I’d still love to see them in my inbox.

That’s it. While most other platforms have emphasized showing you as much content as possible, I hope to see a shift toward platforms that allow people to reclaim their attention and focus on only the most important ideas. This is, after all, the essence of most knowledge work: distilling noisy, mostly superfluous information down to its essentials.

This type of platform would require a paid subscription. That appears to be the only way to align incentives against building another attention trap. The type of media doesn’t need to be limited to text either. This could also work for music or podcasts, with some adjustments.

If you’re interested in building this or something in a similar vein, shoot me a message. I’d love to jam.

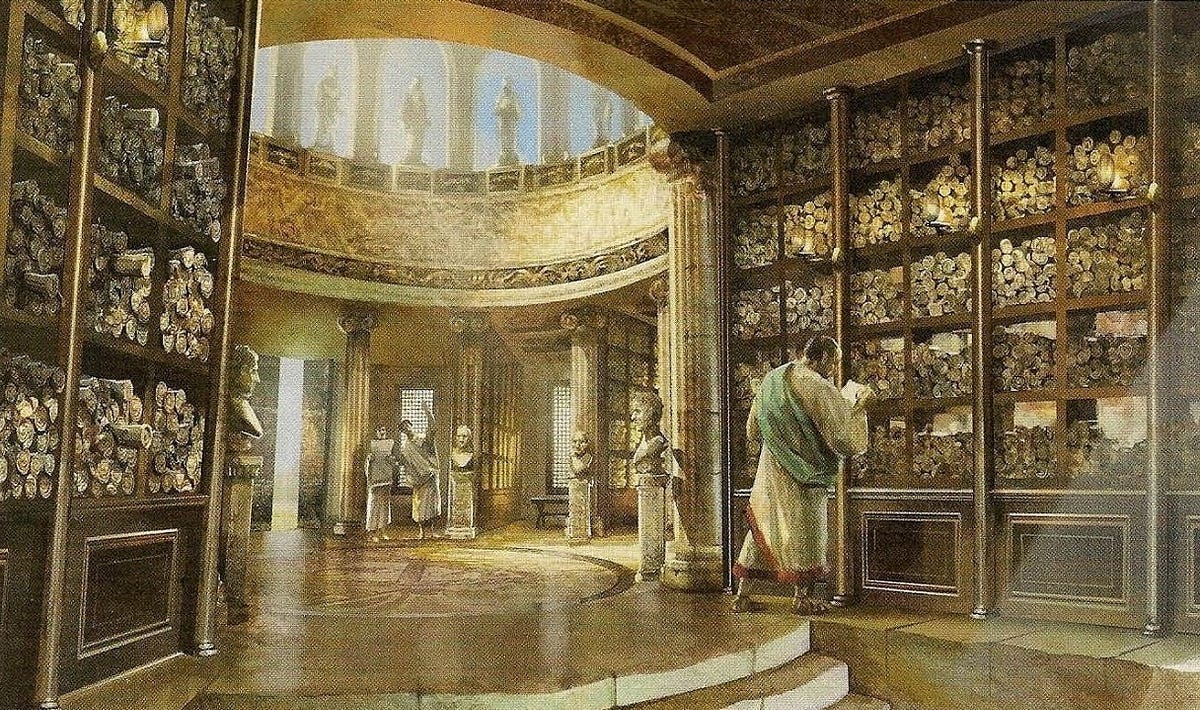

If you make some assumptions, there were roughly 12 GB of text stored in the Library of Alexandria before it burned down (~400,000 scrolls). This was a curated collection. For a comparison point, YouTube has upwards of 140 GB in uploads every minute [1, 2]. This begs the question: are we, as a society, humanly capable of curating this much information?

As an aside, the genre of powerful productivity tools we've seen in recent years seems to be a response to the vast amounts of information people have to keep up with. Note-taking and summarizing apps aren't enough. Notion, for example, can provide a blank slate to help you condense + take notes on an article, but it fails to address the question of whether it is worth reading the original article in the first place.

I love the phrase browser bankrupcy

Great read! This concept reminds me of the same vision the guys behind Path had, just 10 years too early...